A couple of summers ago, we arrived on Ischia in that dead time, too late for lunch, too early for an aperitivo, and famished. The tavola calda just down the road didn’t have much left, but we took some of what there was and then I noticed on the counter a jar of large circular things, with almonds. Presuming them to be some kind of ciambelle, I confidently ordered two of them as a nod towards dessert.

Many of the online food events that have sprung up during the pandemic take place at times that are not ideal for me. An honourable exception is the classes from the Colorado Grain Chain, which generally take place on a Wednesday morning, Mountain Time, an excellent early evening for me. In addition to Julie Zavage’s introduction to the role of rye in a mixed farm. the most recent class featured David Kaminer’s Rye Bread. It was, literally, an inspiration.

My recipe folder is extremely messy. Scraps of paper of all different sizes, some scribbled, some printed, some ripped from newspapers. Truth is, I don’t go to it that often, but when I do it takes far too long to find things than it ought. The upside of that is that sometimes I unearth interesting things that I am not looking for. So it was a couple of weeks ago, when I surfaced a bread recipe from 2007 that I had apparently printed off in 2011. (So glad to be able to report, it is still there: Rustic Flax Seed-Currant Bread – Wild Yeast). For some reason, last week it called out to me.

The finished product is a lot like a ciabatta, and it uses the same double hydration technique to get there. First, you hold back some of the water and knead the dough to a reasonable state of gluten development, about nine minutes in my case. Then you add the remaining water and patiently work to get it all incorporated into the dough. It’s a very handy technique for any highly hydrated dough.

So, here’s my version of Susan’s Rustic Flax Seed-Currant Bread.

Ingredients

420 gm ripe starter at 100%. 105 gm golden flax seeds 155 gm water All of the starter 600 gm water 21 gm salt 4 gm instant yeast 730 gm white bread flour 85 gm wholewheat flour 45 gm whole rye flour All of the flax seeds and their gel 130 gm dried currants

Method

Susan uses yeast in both the starter (a poolish) and the final dough. I wanted to use a leaven so built up my 100% starter with Manitoba flour. I was a bit constrained for time, so I did use yeast for the final dough. When I do this again, which I will, I may try sourdough starter all the way.

Soak the flax seeds at least two hours before you plan to start.

Put the starter in a bowl with 480 gm of the water, all of the flours, the yeast and the salt. Susan used a stand mixer at low speed for 10 minutes. I should be so lucky. I kneaded, hard, for a little more than 9 minutes. Maybe could have done with five minutes more.

The dough then goes back into the bowl and is worked with the remaining 120 gm water, a little at a time, to get all the water into the dough, which will feel very soft and stretchy. This part needs only patience and confidence. It will come together. Once all the water has been absorbed, add the currants and the flax seeds, along with their soaking gel. Mix again, in the bowl, stretching and folding until the additions are evenly distributed through the dough.

Bulk ferment for about 1½ hours, then turn the dough out onto a well-floured counter and do one or two sets of letter folds. Return the dough to the bowl and bulk ferment for another hour.

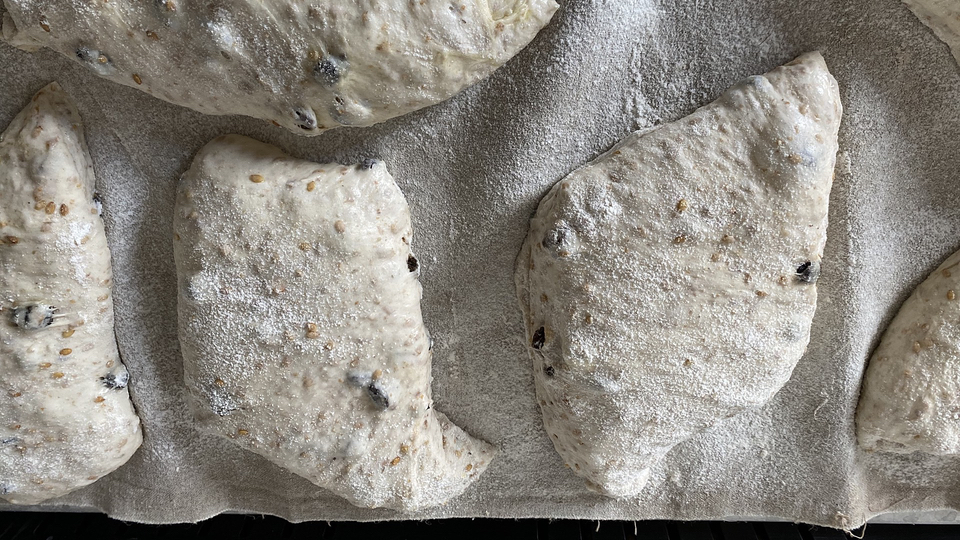

Again, turn the dough out onto a well-floured counter and stretch it gently into a rectangle about 2 cm tall, trying not to degas it too much. With a dough scraper, cut the dough into manageable pieces, transferring each one to a floured couche, without flipping them over. Gently does it. Cover the whole couche with a damp cloth or plastic, supported so as not to weigh on the little loaves.

Proof for about an hour, during which time the loaves will puff up and bubble.

In good time, preheat the oven to 230°C and prepare to steam. A baking stone is a good idea.

When the loaves have risen, prepare a piece of baking parchment the size of your stone, if you have one, or line a baking tray. Lightly sprinkle the loaves with flour and flip them onto the parchment, so the heavily floured side is now uppermost. No need to score.

Slide the parchment onto the stone and bake for 8 minutes with steam. Remove the steam tray and bake another 27 minutes without steam. Crack the oven door open for the final 5 minutes. Susan says to turn the oven off and leave the loaves in, with the door still ajar, for a further five minutes, but I had a second batch to bake so didn’t bother. They seemed fine.

Rest the golden loaves on a wire rack and try to wait until they are properly cool before ripping one open to eat. The sweetish currants make a great foil for the crunch of the flax seeds and the wheatiness of the crumb. A definite winner.

Somewhere, vaguely, I had become aware of a quiet rumbling about turmeric in bread. I don’t think I read any specific recipes, but they were definitely on my radar. Then I found myself with some leftover cooked wholegrain millet on my hands, not enough for a helping for both of us, but too much to toss. Just right, I thought, to add to a bread.

Thoughts wandered, as thoughts do, to millet as a good Indian grain, and from there to turmeric, a good Indian spice, and suddenly, here we were.

Ingredients

200 g white starter at 100%

330 g water

80 g cooked millet

10 g salt

2 level teasoons (10 ml) turmeric powder

130 g wholemeal flour

325 g Manitoba flour

Method

Build your starter according to your preference.

Combine starter, water, millet, turmeric and salt and stir gently to break up the starter a bit.

Add remaining flours and work for about three minutes to get everything incorporated into a good ball of dough. The colour is already quite startling. Cover and leave to bulk ferment.

Stretch and fold every 60 minutes for about 3 hours and then leave until roughly doubled in volume.

Turn out and shape. I made two loaves of about 550g each but you could as easily do one large boule.

Allow to rise for about an hour at room temperature.

Bake at 230°C (450°F) with steam for 24 minutes. Remove steam, if using a pan as I do, lower heat to about 215°C (420°F) and bake a further 22–25 minutes.

Cool on a rack.

The colour is, in my view, drop dead gorgeous. But there is also the unmistakeable slightly earthy aroma of turmeric and also the faintly bitter flavour note in the dough.

Definitely worthwhile. And now I’m seeing turmeric tarallini and turmeric and pepper grissini in the supermarket, so this is definitely a thing.

I’m wondering, are there any turmeric breads I should investigate more fully?

Some praise yesterday for my sourdough bagels made me realise that I had never shared the recipe here. Very remiss of me, so here goes.

The point about bagels, and this I have noted before, is that like ciabatta, the ones you can easily buy are bagels in name alone. For a dense, chewy bagel with a nice shiny crust, you have to make your own, especially if you live in Rome. My recipe is based on one I found 10 years ago in The Fresh Loaf, an invaluable resource for bakers of all stripes. That thread is still going strong, by the way, as people want to make bagels in the time of Covid, which is exactly what I was doing.

So, to business. I’ve made the recipe with yeast, and I also converted it to sourdough, which is what I’ll share here. It is actually very fast, a couple of hours from start to finish, but you could probably do an overnight bulk rise in the fridge if you prefer. I like to start in the morning so that there are fresh bagels for lunch.

Let me note too, that there is no hint of sourness about them. If anything, they are slightly sweet, and note that there is no salt in the recipe.

Ingredients (for 12–13 bagels)

200 gm ripe starter at 100% hydration

360 gm water

40 gm white sugar

9 gm malt powder (probably optional)

1 egg

10–15 ml olive oil

900 gm strong white flour

2 heaped tablespoons brown sugar

Seeds (sesame, poppy, etc all optional)

Method

Build your leaven using your preferred method so that you will have 200 gm of ripe leaven when you plan to bake. My starter is currently good and active, so I just did one build the night before, but you may want to do two builds.

Mix the starter with the water, olive oil, egg, sugar and malt powder. Add the strong flour, mix it up a bit in the bowl and tip it all out onto the counter. At this stage the dough is very dry and there is spare flour everywhere. You are going to have to work hard for 15 minutes to get all the flour incorporated into a very stiff dough. Set your timer, plant your feet firmly and get going on the kneading, using your entire upper body to press, fold and turn, press, fold and turn. The dough will, I promise, come together and will eventually feel alive under your hands.

Bagel dough is stiff and hard work, but ultimately rewarding. This is double the quantity in the recipe, because friends.

After 15 minutes of kneading, return the ball of dough to the bowl, cover with a damp tea-towel and take a break. You deserve it.

The dough now gets a very short bulk fermentation. When I make these with yeast, I follow the instructions and give about an hour. Yesterday, with a leaven, I extended that to an hour and a half, and it was probably a little long. An hour will do it.

Preheat your oven to about 220°C. Prepare baking trays. Pour your chosen seeds, if any, into a saucer.

Shortly before the time is up, bring a large pot of water to the boil, adding two heaped tablespoons of brown sugar.

Weigh the dough and decide how many bagels you want; I generally go for 13 at about 120 gm each. Scale all the individual bagels first, leaving them on the counter. I’m not brilliant at judging dough by eye, so at this stage each bagel is a pile of bits of dough. I give each pile in turn a quick roll on the counter to amalgamate the bits.

Now use both hands to roll each ball out into a snake, slightly tapered at the ends. You are also pressing down the dough, so the bagels aren’t light and airy. My trays fit six bagels, so I do them in batches of six.

When you have rolled all the snakes, form the bagels. Just grab the snake, wrap it around overlapping the two ends and squeeze them together. It isn’t super easy, but you’re not baking for looks alone. Drop the bagels into the actively boiling water. I do it in two batches of three; you don’t want to crowd the pot.

After about a minute, they may float to the surface. If not, gently loosen them from the bottom of the pot with a fish slice or similar. When they float, they’re done. Lift them out of the water and onto a grill.

Carefully — they are hot and squishy — lift them off the grill and onto the saucer full of seeds. Place them on the baking sheet, seeds uppermost, and slide them into the hot oven for 20 minutes. Rotate after the first 10 minutes. The first batch may need a couple of minutes more if the oven is not fully preheated.

And there you are, proper bagels. Knowing how hard you worked kneading the dough, you can indulge yourself when the time comes to eat them. Let me know how you get on.

My thanks to Carol, aka Apprentice, who posted the recipe originally, and to all the people who make The Fresh Loaf such a friendly and useful place.