Many of the online food events that have sprung up during the pandemic take place at times that are not ideal for me. An honourable exception is the classes from the Colorado Grain Chain, which generally take place on a Wednesday morning, Mountain Time, an excellent early evening for me. In addition to Julie Zavage’s introduction to the role of rye in a mixed farm. the most recent class featured David Kaminer’s Rye Bread. It was, literally, an inspiration.

I love the taste of rye. Two rye-containing recipes are in my heavy rotation of recipes, and I’ve played around with a few 100% rye breads here too, with some success. And some problems, the primary one being the top crust lifting off. This, I’ve long understood, is a symptom of The Dreaded Starch Attack. Thanks to this class, I now understand a bit better what this means, and that two important ways to prevent it are to ensure that the starter is good and acidic and that the bulk fermentation proceeds relatively quickly, that is at a warmish temperature.

Rye leaven after one build, beginning with my standard wholemeal starter.

David made his bread look relatively easy (no rye bread is actually easy if you’re used to wheat) so I resolved to give it a go ASAP. There was just one little problem.

What, no bootstraps?

According to David, some old rye bread is an essential ingredient, adding, he said, enormous depth of flavour. But I don’t have any old rye bread. I had old bread, mostly the dried heel of one of my 50% wholemeal sourdough loaves. That would have to do.

Aside from that, I followed the instructions very closely, and I would advise you to do the same, with one big change.

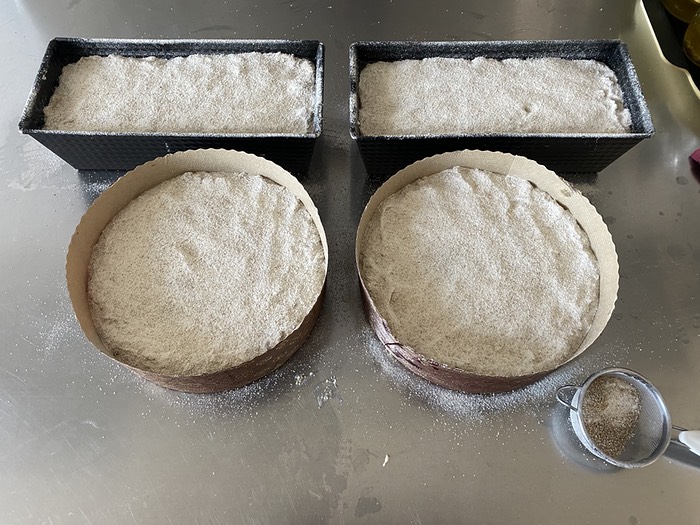

I didn’t really think things through. For some reason, my brain saw the total weight of rye flour (1795 gm) and ingested that as the total final dough weight. So I prepped my two smallish bread tins before the final mix and even when I could see that I had far more dough than I expected still didn’t adjust my expectations. Very silly, and saved only by a couple of paper pannetone moulds that a friend had given me some months ago.

More than twice as much dough as I was expecting.

Sifting flour over the dough leaves a good impression of how sifting gets rid of bran.

It also never fails to amaze me, no matter how often I do it, that less than 10 gm of starter ends up after a couple of builds with enough leavening power to raise more than 4 kg of dough.

I was pretty anxious about the bulk fermentation, because although I used hot water in the final mix, as advised, my final dough temperature was only 26°C (79°F) instead of the 29.5°C (85°F) that David advised. Would it take longer than the 2½–3 hours that he suggested? And if it did take too long, would that usher in the Dreaded Starch Attack? I needn’t have worried. After almost exactly 3 hours the cracks on the surface had opened up and the dough had risen almost to the lip of the tin.

After three hours, dough has risen and surface shows good cracks

Into the oven the tins went; if there was going to be a starch attach, it could take place in the round loaves. And out they came, looking good. The round loaves too. No sign of a sunken top. The Main Squeeze could not wait longer than the following breakfast to slice into the loaf. I managed a little more, 17 hours rather than the recommended minimum of 24 hours.

Straight out of the oven

We both agree it was one of the best breads I have ever baked.

And there it is, 17 hours later; moist, tangy, delicious, nutty, perfect

All I have to do now is to ensure that we don’t scoff it all and leave some old bread for next time. And maybe buy some more tins or halve the quantities. This bread is a winner.

Mentions