My visit to Ostia Antica last year, guided by the wonderfully knowledgeable Farrell Monaco, was destined to end in more than a podcast. There was no way I was going to be able to avoid attempting a panis quadratus of my own, and what better time to make the effort than during Fornacalia?

This is the festival during which ancient Romans made offerings to the goddess Fornax. She was charged with ensuring that when they parched the wheat, which made it easier to mill, the grain did not burn. I did not go as far as making my own mola salsa, but I had to attempt the bread, using Farrell Monaco’s latest iteration for a particularly festive version with fennel and poppy seeds and fresh parsley.

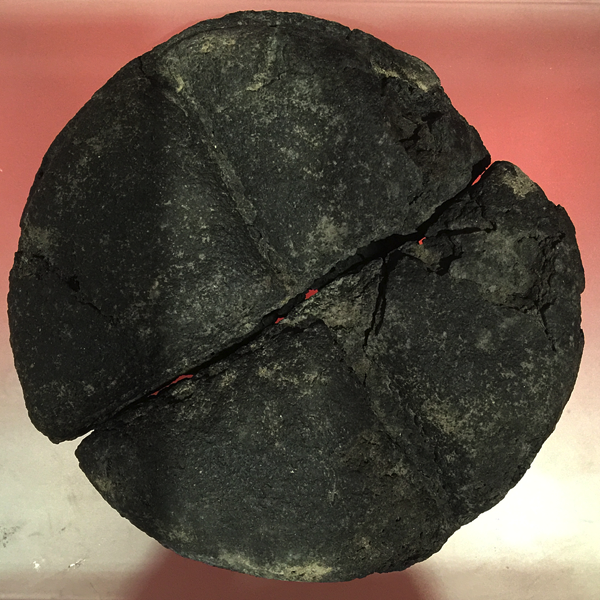

First attempt at panis quadratus. I was too timid with the demarcations, which almost vanished as a result

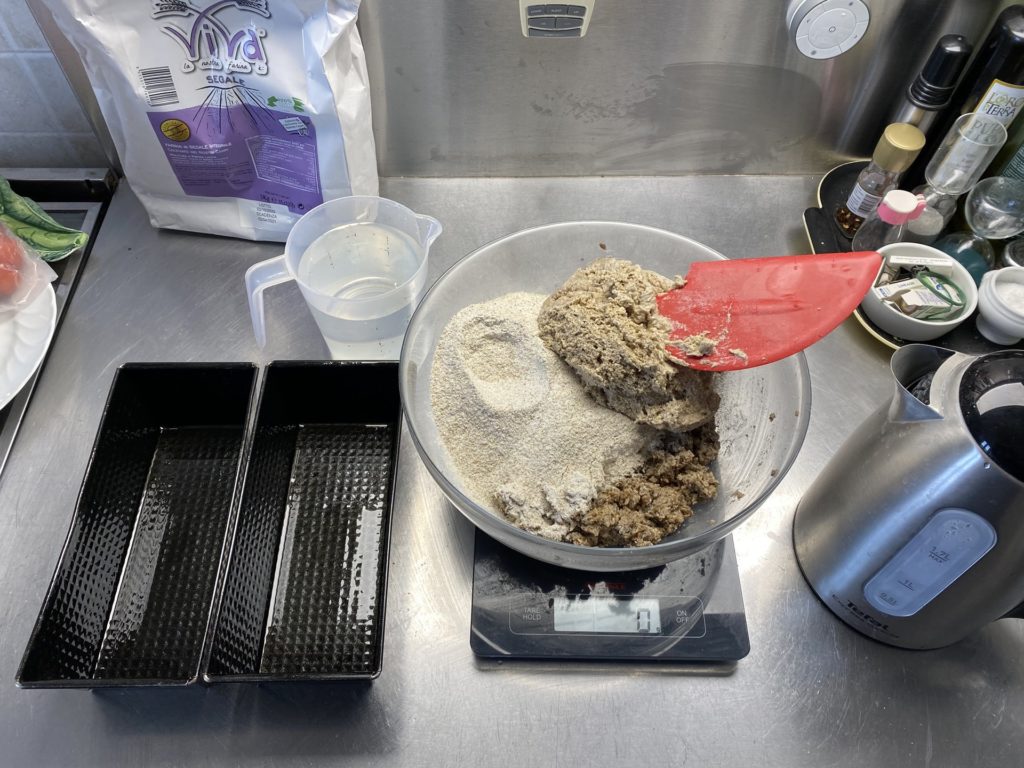

I’m not going to go into much detail, because thanks to her research and experiments Farrell’s articles tell you all you need to know and plenty more besides. The dough is actually very easy for a slightly experienced baker. It is quite stiff, about the same as my usual bagel dough, but being 100% wholemeal never quite becomes as smooth and elastic. Its stiffness, in fact, makes me really curious about the kneading machines that we saw in Ostia. Could wooden paddles really have had any impact on a 55% hydration dough of 100% wholemeal flour? I’d love to see a reconstruction in operation.

Anyway, the relatively small amount of leaven means it doesn’t rise very quickly, so on my first attempt I put it in the fridge overnight because I didn’t fancy staying up into the early hours even to please Fornax. The second time, I started much earlier in the day — about 8:00 am — and had a baked loaf by 5:00 pm.

The tricky part is not the dough but the shaping and handling. The key elements of panis quadratus are the belt around its equator and the divisions pressed into the top to demarcate the sections. Tying the string, of finest Italian hemp, was a little bit fiddly for my fat fingers. And on the first trial, I was much too timid about pressing my reed (bamboo, actually) into the top of the dough. As a result, just as Farrell foretold during our visit to Ostia, the oven spring all but obliterated the marks. The next time I bore down on the bamboo and the marks survived well. And even though mine were the only loaves in my oven, for the finishing touch I did mark them with the bread stamp Farrell sent me.

As for the taste, it really is rather good. The bread is by no means light and fluffy, but it is not hard to chew either. It is soft, without being fluffy, and the taste of the poppyseeds and especially the fennel, comes through in every bite. I really like it with some well-aged sheep’s milk cheese, although it is also very good with a little butter and honey.

Fornacalia ends tomorrow. I reckon I will be in Fornax’s good graces for another year.