It’s a long story, one that I hope will appear on the podcast in the fullness of time, but suddenly we have a supply of superb hummus and other like-minded goodies here in Rome. Not so the pita. I mean, it’s OK, as a shovel or wrapping, but not for its own sake. Nothing for it, I thought, I’ll just have to bake my own.

It’s a long story, one that I hope will appear on the podcast in the fullness of time, but suddenly we have a supply of superb hummus and other like-minded goodies here in Rome. Not so the pita. I mean, it’s OK, as a shovel or wrapping, but not for its own sake. Nothing for it, I thought, I’ll just have to bake my own.

In this I was encouraged by friends who seem to do it all the time, posting photos of the exquisite results. Off, then, to Claudia Roden’s A New Book of Middle Eastern Food and her recipe for Khubz (Eish Shami), which, she delightfully tells me, “is more commonly known in the West as Pitta bread”. I hope she won’t mind me sharing my interpretation here.

The dough is simple:

- 500g strong flour

- 300g tepid water (60%)

- 4g salt (8%)

No time to do it with a leaven, so I went the direct route and added one teaspoon of dried yeast. (It should probably be more, but I did have time to allow for a longer rise.)

The joy, if you’ve been messing around with highly-hydrated doughs, is in the 15 minutes of kneading. I tend to go by counts to 100, with a little rest after each burst to see how things are going, and it is wonderful to watch and feel as the dough becomes alive and elastic beneath your hands. A wet dough, as it becomes stronger and more structured through a set of stretch-and-folds, is also a delight, but it doesn’t offer quite the same satisfaction as a proper knead.

With a lovely, lively ball of dough in your hands, dribble a short thread of olive oil into a bowl and wipe it about with the dough to just lightly coat the surface of the dough. Cover with a damp tea-towel and leave in a warm place to double, about two hours.

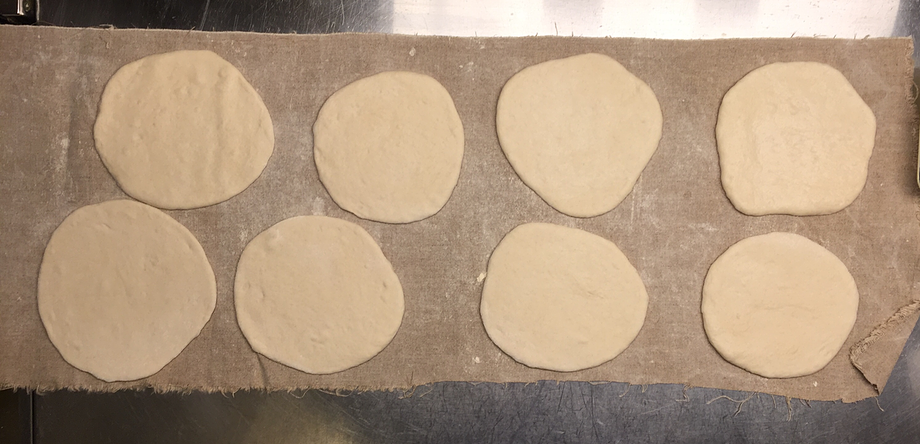

As you gently persuade the dough out of the bowl, pause again to marvel how extensible it has become. Resist the temptation to “punch” the dough down; a little gentle kneading is all that is required. I divided the dough into 8 pieces of 100g (Claudia advises “the size of a large potato or smaller”) and roll each one out on a lightly floured surface to a disk of around 0.5cm thick. Place these on a well-floured couche, cover with plastic film and the damp cloth, and leave again for a second rise of about another two hours.

Preheat the oven to maximum (in my case around 240°C) and place a lightly oiled (or non-stick) baking tray in to heat up. Also, prepare to steam. When you’re ready, add the water to your steam container. Then, working quickly, gently lift the rounds from the couche and onto the tray. Gentleness is crucial here; any rough handling and they won’t puff up in the oven. Spray gently with cold water “to prevent them from browning,” slip them into the oven and shut the door.

[B]ake for 6 to 10 minutes, by which time the strong yeasty aroma escaping from the oven will be replaced by the rich earthy aroma characteristic of baking bread – a sign that it is nearly done.

Do not open the oven door during this time.

I gave them eight minutes. Eight long, fraught, anxious minutes. I needn’t have worried.

As I said on Instagram: “OMG. It worked. Thanks Claudia.”

Cool the little flatbreads briefly on a wire rack and if you have any left over, pop them into a plastic bag. Anathema for most breads, but these need to stay nice and soft.

I can also attest that they reheat beautifully in a hot cast-iron frying pan.

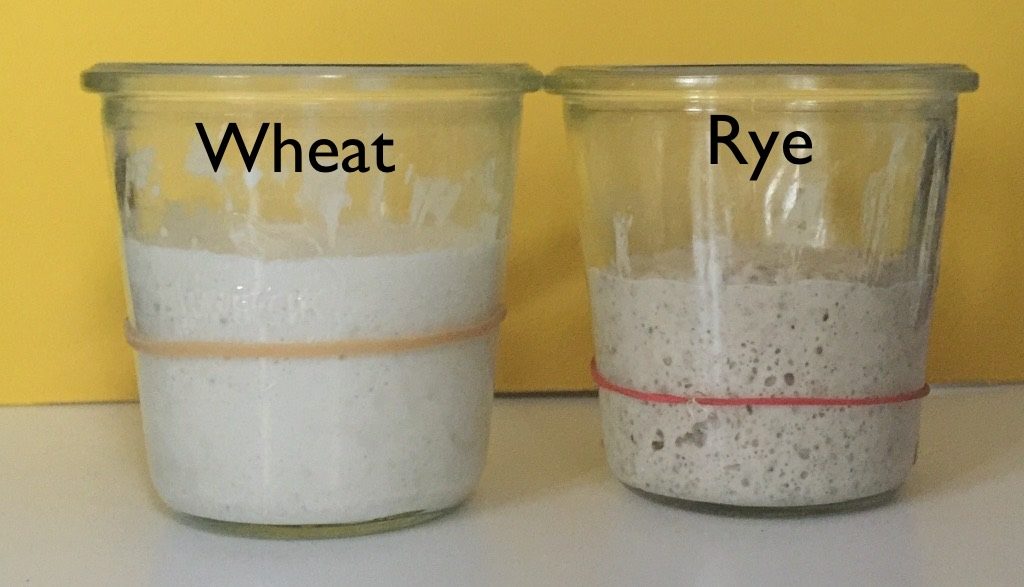

As a result, I was ready to begin the recipe proper, on Thursday morning, with the natural rye sponge. Five grams of starter seems far too little, but it did its job, and of course one of the fine side-effects of too much starter is

As a result, I was ready to begin the recipe proper, on Thursday morning, with the natural rye sponge. Five grams of starter seems far too little, but it did its job, and of course one of the fine side-effects of too much starter is