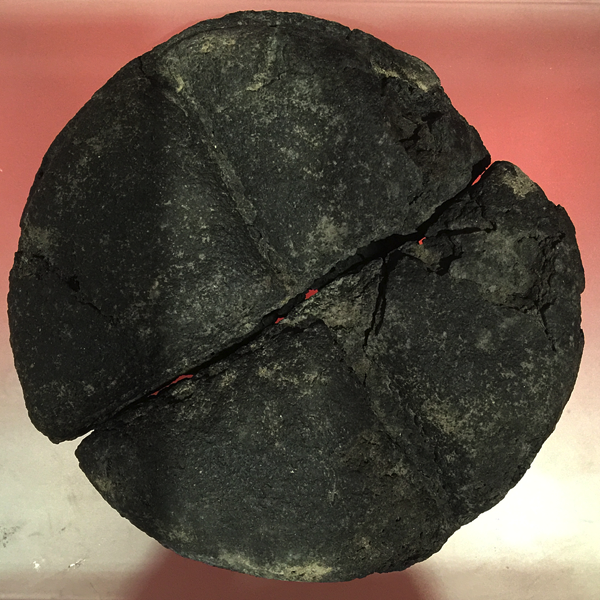

Panis quadratus, carbonised at Pompeii

When first I came across the ancient Roman festival of Fornacalia, , it seemed to me an ideal opportunity for newly inspired bakers at home and in bakeries to celebrate their art. Two years later, I even left a desperate little plea to that effect in a forum I frequented. It died a death, as it has most years subsequently, a notable exception being Dan Etherington’s post . Like my leaven, though, which refuses to die, I’m going to give it another go.

I’m emboldened to do so by Chris Aldrich, who took it upon himself to anoint me . As such, it is my duty to proclaim Friday 16 February, an auspicious day for me, the day to celebrate Fornacalia, using the hashtag #fornacalia.

I’ve been doing a little research of my own, torn between the Scylla of tried-and-tested and the Charybdis of new-and-appropriate, and I think I have come to a decision.

Stay tuned. And spread the word.