I have not made pizza since moving to Rome a long time ago. Well, why would I? With all the pizza places shut, however, there’s only one way to get a pizza. Make it.

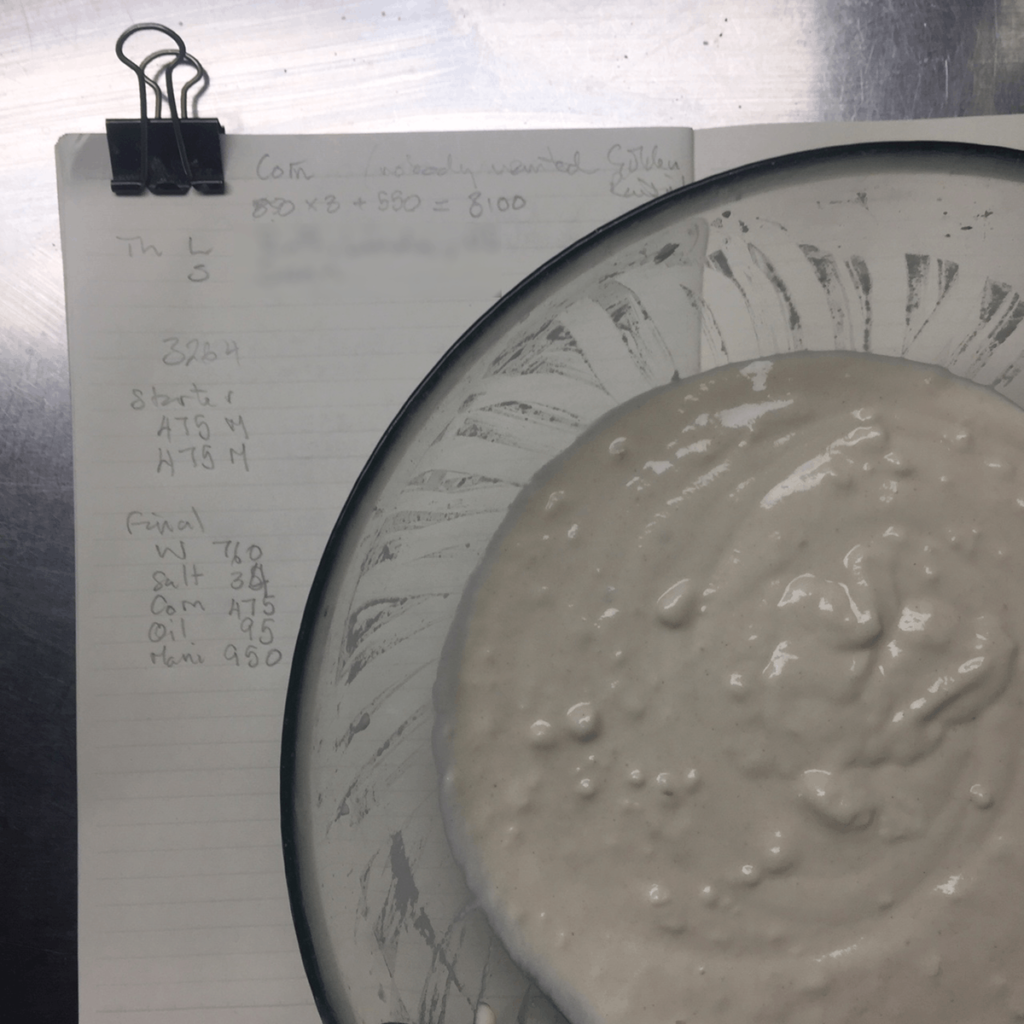

In this I was inspired largely by my friend Dan’s , adapted to my own preferences. The first of those is to use one of my standard leavens. I chose the wholemeal one, because it offers an easy way to have one-third of the flour be wholemeal.

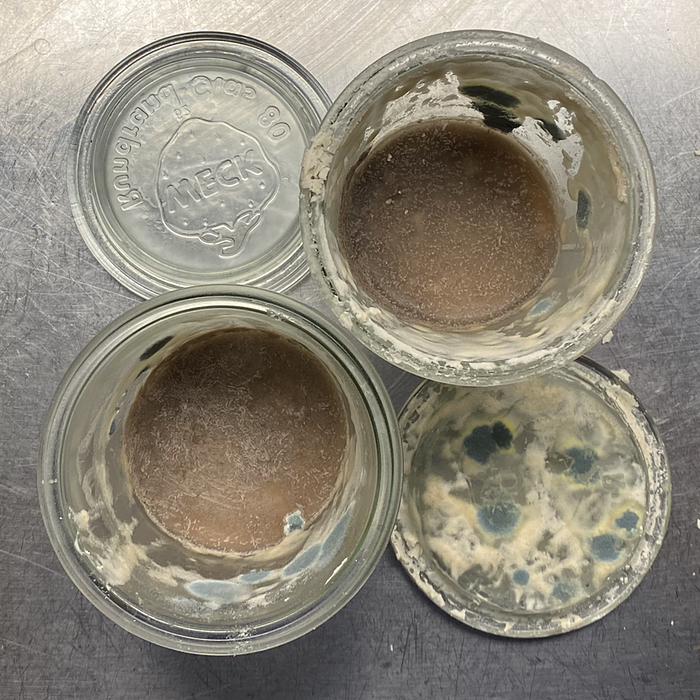

Friday evening, 10:00 pm, I fed the starter with 75 g wholemeal and 100 g water.

I reckoned I would need 600g of dough for my tray, which is about 28 x 40 cm, at 70% hydration. So:

- 355 g flour

- 245 g water

- 7g salt, and

- 20 g olive oil.

Dan uses one third each of strong flour, all-purpose flour and light spelt. My wholemeal is pretty strong, so I went for 100 g each of wholemeal (in the leaven) and strong flour and 155 g of all purpose.

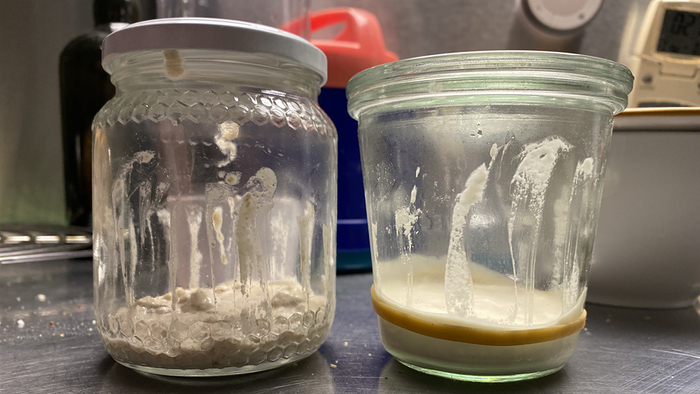

Saturday morning, 11:45 am, I removed some starter for next time and mixed the leaven up with the remaining water (170 g) and 100 g of all purpose flour to make a sponge, which I covered with a plate and left on the counter to do its thing for about 4 hours.

Saturday afternoon, 3:30 pm, with the sponge bubbling a bit, I poured about 20 g of olive oil on top and mixed it in with a spoon.

Add the rest of the flours and the salt and stir roughly about until you can tip it out onto the counter. I shove it around with the heel of my palm to bring it all together then scoop it up with a scraper and dump it back in the bowl.

At 10 minute intervals, I tip the dough out onto the counter, give it five or six quick kneads and return it to the bowl. Do that three times, after 10, 20 and 30 minutes. Then leave the dough to bulk ferment. I like to do some stretch and folds each hour thereafter, with coil folds to finish the second and third sets.

Saturday evening, 7:15 pm, and it’s almost time to eat, so I fire up the oven to max. I think it reaches 240°C. Who knows? Dan rolls his dough, but he knows what he’s doing. I prefer to stretch by hand, tackling it over three or four sessions to allow the dough to relax a bit between each stretch. Manual stretch also allows me to make the crusts a little bit thicker.

After the first stretch, I start the sauce. Half an onion and a clove of garlic, thinly sliced, sprinkled with a pinch of salt and sweated gently in a little olive oil for about 5 minutes. Then I add a good grinding of hot pepper flakes, a can of peeled tomato bits and a good teaspoon of dried oregano. Bring to the boil and then turn the heat down low.

Time to stretch the dough out again.

While it is relaxing again, and the sauce is simmering, I slice the fresh tomatoes and the mozzarella. Then a final stretch of the dough, this time into the pan. It has a slight lip, which is great because if necessary you can flip a bit of the dough over the edge to stop it stretching back.

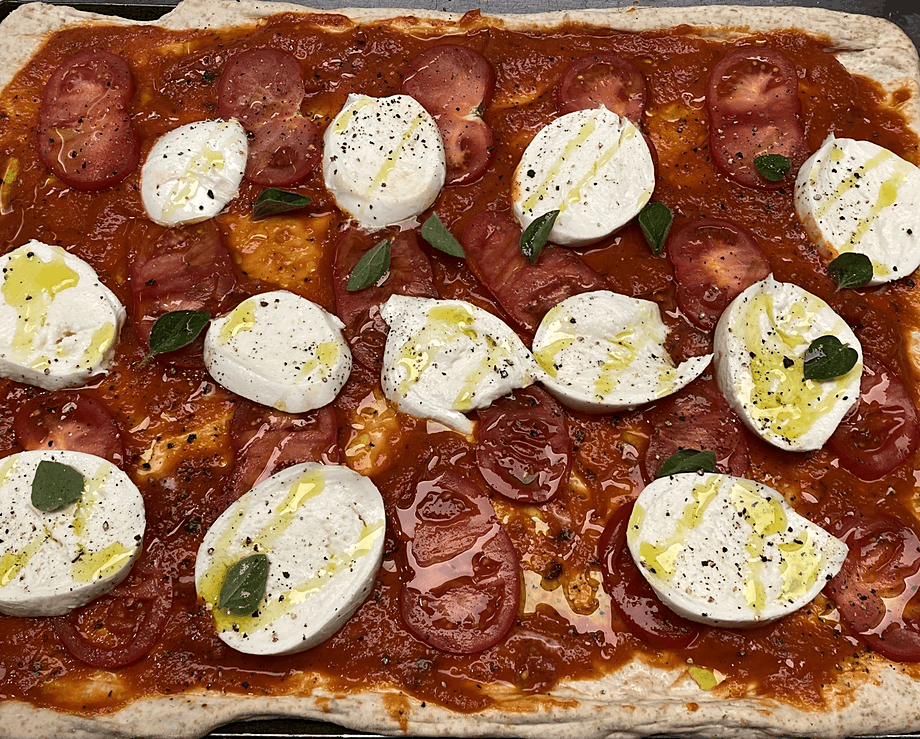

The sauce comes off the heat and gets whizzed with an immersion blender. By now the oven has been preheating for about 40 minutes and is plenty hot enough. So I construct the pizza, trying to spread the sauce evenly but not too deeply and then arranging mozzarella and tomato slices on top. Although we had no basil, we did have a bit of fresh marjoram, so a few leaves went on too. Then some black pepper and a quick spurt of oil and into the oven.

About to go into the oven

Straight out of the oven

I rotate the pizza through 180° after about 9 minutes, and take it out after 15 minutes. Scissors, I’ve learned, are far and away the easiest way to cut portions, the remainder going back into the oven, now off, to stay warm.

Ready to eat

And though I say so as shouldn’t, it was very, very fine.

What would I change? Definitely cook the sauce a little longer on a higher heat to thicken it a bit more. Maybe only 500g of dough, although then stretching it to fit without tearing it might be an issue.